by Beck Pulis; Denver School of Science and Technology (Denver, CO)

“I think stress definitely had negative impacts on me,” says Rachel Wiggans, age 18. “I usually got sick more often because of stress. I always got sick around finals, and suffered from less sleep during my most stressful times at [Denver School of Science and Technology] as a junior and first trimester senior year.”

“Stress has always been a love-hate relationship for me,” says Jack Gurr, age 18. “I’d be lying if I told you that it wasn’t the reason why I sat down and did the homework I never felt applied to my future. Whenever I took fast-paced exams, like the ACT, SAT, or AP tests, I would constantly feel a knot in my stomach. Ultimately, one of the major factors behind my work ethic was due to stress.”

Nor are Rachel and Jack alone in feeling stressed. In 2013, the Harvard School of Public Health reported that 38% of parents said their child has experienced an unhealthy level of stress. Parents said sources of this stress include pressure from the school to excel academically (42%), quantity of homework (43%), bullying (30%), and relationships with other students (33%).

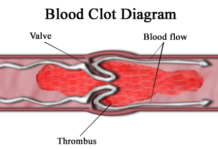

According to the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine’s teen health guide published in 2010, our body responds to stress by activating hormones such as adrenaline that filter into our bloodstream. The prefrontal cortex, the part of our brain that analyzes stressful situations and controls the response, isn’t fully developed in adolescents. As a result, teens have elevated and more rapid responses to stress. Some of these responses include: sped up heart rates, breathing rates, and/or the liver releasing too much glucose into the body’s bloodstream, which can eventually lead to hypoglycemia. Mayo Clinic’s information on hypoglycemia states that it has a high long-term mortality rate, but over time people can develop blurred vision, shakiness, and excessive sweating.

The American Psychological Association reported on two main types of stress. The first is acute stress, which is highly manageable and can occur in anyone’s life. The main symptom is a fluctuation in emotions. The other is chronic stress, which is a result of prolonged stress and has the most damage when people become accustomed to it. Chronic stress can cause heart attacks, stroke, and sometimes cancer.

In the Harvard’s study, it was found that if a stress response goes on too long, in cases of bullying or prolonged stress over school, the immune system becomes weaker.

A 2013 S\dtudy led by Daniela Kaufer, the associate professor of integrative biology from the University of California at Berkeley, found that stress in small doses increases cognitive and mental performance. Kaufer’s group conducted an experiment with rats and found that stressful, short-term events allowed for the stem cells in their brains to mature more adequately. Two weeks later, the rats’ mental performance was much higher.

The experiment measured the amount of glucocorticoid, a stress hormone, in the rats’ bodies. When this hormone is in high doses, the production of new neurons is inhibited. Rats that were found to have increased levels of the glucocorticoid hormone showed signs of obesity, heart failure, and a lack of social interaction. In small amounts, this stress increased cognitive ability as short term events help animals adapt; animals develop their memory so as to remember where a stressful event occurred and be more proactive in their response in the future.

So, what is a healthy level of stress? Kaufer’s study reported that, in humans, a high level of stress is directly related with the amount of glucocorticoid stress hormones released. These hormones inhibit the hippocampus, the part of the brain responsible for short and long-term memory, from producing neurons. Reduced neuron production can cause obesity, heart disease, depression, and memory loss – signs of someone being under too much stress.

“Junior year has taken such a toll on my brain. I just got headaches from the overload of stress, but thankfully I had running to ease my pain,” says Rainie Toll, age 17, a high school student who runs cross country. “I know that stress is imperative to my motivation as a student, but the level I was at just wasn’t healthy. To remedy that, I made it a point to run every day at 6:30 in order to lower my stress level.”

This aligns with a study conducted by Harvard’s Health Department. In the study, it was found that aerobic exercise decreases the amount of hormones, such as glucocorticoid, adrenaline, and cortisol, in the body. At the same time, more endorphins are released. These endorphins reduce pain and contribute to happier emotions. Along with exercise comes with improved fitness and better a better physical appearance. The same study added that this physical improvement is beneficial to stress levels because it facilitates a happier lifestyle.

Dr. Jim Stephens, the Senior Project Coordinator at the Denver School of Science and Technology, takes a nuanced look as to how the school system can be improved to reduce stress in students. “I think the key to finding an appropriate level of stress is to redesign the school system. There’s so much structure and coddling in middle and high school years. The reality is that when college comes around, our students will overdose on freedom and stress. The stress won’t come from lots of work, but poor management of that work. Essentially, the freedom shouldn’t all come at this time, but be a gradual release – starting from 6th grade.”

Beck Pulis

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License