He broke his neck at age 19 and can’t move anything below his shoulders. Nearly 24 years later he’s grateful for his power wheelchair, a modified van he can drive, the continuing care-giving of his parents and especially for his teeth.

“I would have a lot less independence if I didn’t have good teeth. I use them to attach cuffs to my hand for writing, typing, driving, brushing my teeth, everything,” Skip Bryan, now a 43-year-old quadriplegic, tells SciJourner. “And, of course, there’s the whole eating thing. When you think about it, my mouth is about the only thing I can still move normally.”

Having good teeth is more important for the disabled population than it is for the rest of us, according to James Bubenik, a dentist in Town & Country, MO, who reports that about half of his patients have a disability. “Disabled people get a great deal more enjoyment from eating than we do. It’s one of the few pleasures in life we don’t take away from them,” he says.

Over 100,000 Missourians have a developmental disability, that is, a disability before age 22. Other disabling conditions develop later in life. "More than 40 million Americans–about one in seven–are now disabled., and that number is likely to increase significantly in the next 30 years as the population of baby boomers ages, since age itself is a major risk factor for disability," according to 2007 article in American Medical News (AMN).

|

Sidebar: Tricks of the Trade Fear of the unknown and mistrust prevent some disabled patients from getting the care they need from physicians and dentists. So doctors like James Bubenik, a dentist in suburban St. Louis, have turned to behavior modification to help these disabled patients control their impulses and cooperate with procedures in order to receive medical treatment. Behavior modification is a method of teaching a behavior then further shaping it through the use of reinforcement or lack of it. It is based on the principles of operant conditioning, developed by B.F. Skinner in the 1930’s. “Skinner discovered that the rate with which a rat pressed a bar depended not on any preceding stimulus, but on what followed the bar presses,” according to the B. F. Skinner Foundation. In other words, animals will perform a desired task for a promised reward. His theory has since been adapted to humans in the form of behavior modification. Bubenik says he has successfully used behavior modification with some of his patients for many years. In fact, he stocks boxes labeled “reinforcers for girls” and “reinforcers for boys” in his office. “All human beings have their behavior shaped by everything in their environments no matter what their level of cognitive functioning, from the profoundly mentally retarded to genius level,” he says. In the last hundred years the principles of behavior modification have been standardized to the point where now discovering an individual’s reinforcers is the most challenging part, he adds. Once they are observed and the behaviorist controls them, the rest is almost rote. Normal humans have very complex systems of motivation and reinforcement, such as the desire for prestige, approval from a loved one or self-satisfaction. The very young and those with mental retardation, however, respond to primary reinforcers such as food, comfort or anything a person naturally desires without being taught. For example, one of Bubenik’s patients, Robert, was a 38-year-old male with severe mental retardation. Though he appeared not to have any fear issues, he refused to sit in the exam chair. Through trial and error, Bubenik discovered that a small drink of soda was the key to getting the man’s cooperation. In fact, tiny sips of soda at frequent intervals helped the patient complete the entire dental visit. Now that Bubenik has been doing it a while, it doesn’t take him long to figure out which reinforcers will work on a patient. “I usually enter the exam room prepared with 10 things I expect will work based on talking with the parent or caregiver, such as some snack foods, an intriguing toy, bubbles, or a distracting video controlled by me,” he says. B.B. |

"If one considers people who now are disabled, those likely to develop a future disability and people who are or will be affected by the disabilities of family members or others close to them, it becomes clear that disability will eventually affect the lives of most Americans," Alan M. Jette, director of Boston University's Health and Disability Research, said in the AMN article.

Many disabling conditions surprisingly include a dental aspect. “Damaging oral habits can be a problem for people with developmental disabilities,” according to a 2010 article from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR). Some common problem habits are grinding teeth, holding food in the cheek, breathing through the mouth and pushing the tongue straight out when swallowing. Other damaging behaviors include picking at the gums or biting the lips; “rumination, where food is chewed, regurgitated and swallowed again; and pica, eating objects and substances such as gravel, sand, cigarette butts or pens,” the NIDCR reported.

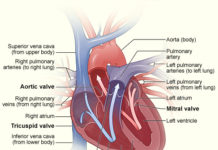

In addition, “periodontal (gum) disease occurs more often and at a younger age in people with developmental disabilities. Contributing factors include poor oral hygiene, damaging oral habits, and physical or mental disabilities,” according to the NIDCR report. Also, overgrowth of gums is caused by many medicines including those for convulsions and high blood pressure, and this increases the risk for gum disease.

The consequences of untreated dental issues are emotional, physical and behavioral for disabled people. Tooth pain causes depression, anxiety and acting out in this group, Bubenik said. “Those with really profound problems stop eating. Severely disabled patients can’t express that they’re in pain, so doctors and caregivers start looking elsewhere for a cause and infer causation, but it’s because their teeth hurt. Preventing dental diseases by using a toothbrush and dental floss effectively is nearly universally lacking in disabled populations.”

“If they’re missing several teeth in back, they don’t chew the food properly, and they have indigestion,” he added. Others may be missing a number of teeth in one area, which would usually be treated with a denture, but for disabled patients a denture may not be feasible due to cost, an inability to get used to it, pain, or losing or breaking it more frequently than average patients.

Medicare does not cover dental care needed for the health of a patient’s teeth, such as routine checkups, cleanings, or fillings, and it will not pay for dentures, according to the Medicare Rights Center. State Medicaid programs, including Missouri and Illinois, are rapidly eliminating dental coverage, Bubenik says.

Losing teeth in the front causes disfigurement, Bubenik says, “which perpetuates the stereotype that those with handicaps aren’t as worthy as other people, but in some cases they just can’t afford the denture.” He adds that almost every disabled person he knows has received trauma to their front teeth because they tend to have problems with gait, not having the capacity to think about the consequences of their actions, etc. These are expensive teeth to fix, he adds.

“People with disabilities are overwhelmingly poor; their level of education tends to be low and they are more likely to be unemployed or employed only part-time; many depend on public programs for much of their income and services,” according to the NIDCR. And they must depend on their caregivers to obtain the kind of care non-disabled people can get by just picking up the phone.

“I’ve been lucky,” Bryan says. “I’ve been able to afford good dental care so far. But as I get older and my income decreases, I’m not sure what I’ll do. My teeth are a priority, but so is having heat in my home.”

This is a really important issue, thank you for showcasing this. What is the percentage of developmentally disabled individuals who are covered by private insurance and those covered by Medicare?